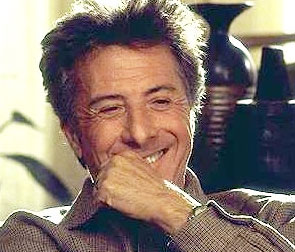

Dustin Hoffman Exculusive - Moonlight Mile

HOFFMAN GOES ALL OUT TO PLAY GRIEVING DAD.

Dustin Hoffman/Moonlight Mile Interview by Paul Fischer in Toronto.Dustin Hoffman is every bit the movie star: charismatic, charming, knows how to work a room, yet remains unpretentious in the process. Commenting on how busy he is at the Toronto Film Festival where he is enthusiastically promoting his latest film Moonlight Mile, and his first major movie since his supporting role in 1999's The Messenger, Hoffman quips: "Well this is aptly called a junket, for both of us. I have never been to a house of prostitution, but I understand that you get in more than seven minutes," he jokingly says of the limited time we have to spend chatting with an actor who loves to talk.

Hoffman is also known for his thoroughness in preparing for a role, and no more so than in Moonlight Mile. Here he plays the grieving father of a daughter killed in a freak shooting. Near the end, he says goodbye to his daughter's would-be fiance (Jake Gyllenhaal), then immediately turns away from the camera. When asked why he turned his back, there is a pause as Hoffman's memory of the day's shooting takes on an emotional tone. "I remember that moment exactly, I'll tell you the story. I like to block out all the business I'm going to do in a scene first: ?Okay, I'm packing up my office, I see a photograph of my daughter, I cross to show it to Jake, I say goodbye.' I walked through it a few times, then Brad [Silberling, director] said, ?Let's try one for the camera.' So I go through the scene, I'm not expecting anything, I stand in front of Jake, and suddenly I'm completely overwhelmed, out of nowhere I'm weeping, weeping, I can't stop, and I have to turn away." As he's saying this, Hoffman's voice breaks, and one realises that the great actor's memory of that day is making him cry as he continues: "Brad is saying, ?Where are you going?' and I'm saying, ?It's over Brad, the scene is over, I can't do it again, I don't even want to look at him any more.' And that's the take we used."

"I have six kids and only two of them are left at home, They're all healthy, but nobody talks to you about the empty bedrooms, nobody warns you what that feels like. You spend your whole life looking over here, at your career, and then one day you wake up and realize you should have been looking over there and it's too late."

Hoffman's tears stop flowing and he is unapologetic that memory of aspects of his own life can bring on an emotional response. "Hey I'm older than you are", he exclaims, smiling. "When you get to be my age, you'll find out what an emotional mess YOU are. Female ormones surface more and more and you're gonna realize all of the emotional life you have missed by being tied to a maniac called testosterone. It is not a bad feeling to be emotional," he says, with increased laughter and amidst the tears.

The tears do stop to flow but there is a distinct feeling that Hoffman is not acting, yet there is no doubt that he has always taken the job of acting seriously, too seriously some may argue, to the point at which he has often been labelled as ?difficult'. The actor does not necessarily disagree. "Well difficult usually comes from a cast member or from a few directors and producers," Hoffman explains, with a deliberate and articulate slowness. "I think the most insulting thing you can do to a director is to challenge when he or she is satisfied with your interpretation. You say ?No it is not right yet'. You are not there to tell them something isn't right," Hoffman says, his voice rising slightly. "There are those directors that like actors and there are those that tolerate them and they actually fall into one or two categories: Those directors that want to be surprised by an actor, and those that want to control and want to know in advance what you are going to do and don't want you to overstep that boundary. I think I learned since those early experiences, a couple of lessons to kind of avoid the trappings that I had early on, because I don't have them anymore. That is, to establish my credentials early on, rather than fall into what I initially did, which was: You are the kid and they are the father. Or you are the wife and they are the husband: Don't tell me how to make this movie, do what I tell you and I'll make you look beautiful. I'll light you well. You are going to give a great performance, leave the driving to me. Many actors or stars, male or female, will tell you that we learn to do what wives used

to do, and sometimes still do: Honey, this was your idea, and the fact it, it is a very tough job to be a director, it is a terrible job. I think I

have more understanding of that. If they really care about their work, they take an easel, they put it up, they have looked at the landscape, they have picked out what they want to paint it, they have put their painting on the easel, and they start to paint and suddenly realize that the easel is on a railroad track and they hear a rumbling, so they start painting faster and faster, faster and faster than they want to do, faster than the art is dictating, and they pull that canvas off just before the train hits, and that is their movie, you know, and that is the reality they are faced with."

Yet ironically, Hoffman is about to step into the director's chair for the first time, and possibly take those experiences and learn from them as a director? "No, I'm going to fire myself the second day", he quips.

Difficult or not, Hoffman is every bit the movie star, and these days, mentor and father to those fortunate enough to share a set with him. On the last day of shooting Moonlight Mile, Hoffman presented Jake Gyllenhaal with a book from a rare book store. It was a book on acting by Stanislavski, which Hoffman inscribed. Asked whether an older actor ever did the same to a younger Dustin, he smiles, as he recalls a significant moment in his working life. "I did a movie called Marathon Man and it was one of my best memories.

I had become very friendly with [Laurence] Olivier during the making of it. He had five different illnesses which should have taken him out ten to fifteen years sooner before he was gone. He was on medication that was so strong, he couldn't memorize three lines or four lines in a row, and this is a guy who has held Shakespearian roles in his head when he was doing repertory, and we'd talk about how he'd do that. And we would talk a lot about Shakespeare, and he kept saying, ?Oh my dear boy, you have to do Shakespeare.' He could've been a scholar, he knew the period, and he was a historical scholar, at least from my view point. So the movie is over and I'm sitting there in my rented house and he says, ?Dear boy, I know you are finished, but I'd like to drop something off to you.' "What it was, was a leather bound collection of Shakespeare's completed works, notated by Olivier. "I know he liked to perform, he was that powerful of a resence, but he loved it, and he sat with me after, going through this anthology, reading out passages. It was an extraordinary moment."

Dustin Hoffman, who eventually won two Oscars for Kramer vs. Kramer and Rain Man, has forged a career that few actors dream off. But it all began with The Graduate, for which he was nominated for his first Oscar, and three decades on, he finally addresses that age-old question: Will there ever be a sequel to? "Yes, Nichols had a great idea a few years ago. He said that they are all alive, Katherine Ross, Anne Bancroft. He said: I think Benjamin directs television commercials and I know where he was coming from. That whole Benjamin generation was the generation that was soon to become the baby boomers, and he went right back to doing what he was projecting from his father, in other words, material things, substitute for love or substance."

Always intent on making the perfect exit, Hoffman finally poses a question of his own by asking my age. When I tell him I'm 45, he says: "I would take what you are backwards. That's how old I am!" It's pure Hoffman.

MORE