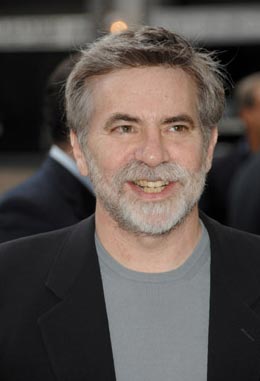

Dan Klores Director of Crazy Love

Dan Klores has directed and produced four award-winning documentaries in the past five years - he is currently shooting his fifth film.

The New York based Dan Klores, who founded Shoot The Moon Productions in 2005 has exhibited a special knack for storytelling largely based around the concepts of love, loss and the underdog. His credits include "The Boys of Second Street Park" (Showtime) and "Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story" (NBC Universal), which both premiered at The Sundance Film Festival. In addition, Dan Klores directed "Viva Baseball" (Spike TV), a look at the struggles, conflicts and achievements surrounding the Latino experience in America's Pastime. The film was awarded the Imagen Award as the best documentary for television and film and the 2006 BANFF World Television Award for Best Sports Program.

Most recently, Dan Klores directed and produced "Crazy Love," a true story of the rollicking, obsessive and violent relationship between a married man and single woman that dominated the nation's headlines almost 50 years ago. "Crazy Love" also premiered at Sundance. It went on to win the Jury Prize at the Santa Barbara Film Festival and will be released theatrically by Magnolia Films on June 1st.

"Black Magic," Klores' next film is a four hour, two part series on the injustice which defined the Civil Rights Movement, as told through the lives of basketball players and coaches who attended Historical Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). "Black Magic" will premiere on ESPN in March 2008.

Additionally, Dan Klores is producing the feature remake of "Ring Of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story" (Sony/ Paramount) with Scott Rudin. The film will be directed by Tony Award winner George C. Wolfe and was written by Stephen Adly Guirgis.

Other producing credits include "City By The Sea" (Warner Bros.) starring Robert DeNiro and Frances McDormand, and Paul Simon's Broadway musical, "The Capeman."

Dan Klores, who resides in Manhattan with his wife Abbe and their three young sons, recently completed his first play entitled "Little Doc" which will be directed by John Gould Rubin and is scheduled to be presented off off Broadway in the fall of 2007. His second play - "Myrtle Beach," a one act about a conversation between the Head and the Torso of the same American soldier killed in Iraq, will be part of the upcoming Naked Angels series of one acts at the Duke Theater, beginning April 12th.

An accomplished writer, Klores authored Roundball Culture (Stode Publications, 1980), and, has written for Esquire, New York Magazine, The Daily News, The Village Voice and Southern Exposure.

INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR DAN KLORES

Tell us about the genesis of CRAZY LOVE, and your relationship to the material.

Dan Klores: About four years ago, I read an article in the New York Times about Burt and Linda, and it reminded me of the whole story, what I remembered from when I was nine or ten years old in 1959. I was in the middle of cutting Viva Baseball, and I was considering what to do for my next project. So I was drawn to it initially because of my own memories...."Oh, that's a good story." It had been a big tabloid story. So I looked for Burt and I had to look no further than the phone book. He was listed. I had lunch with him and Linda-I took a friend with me-to a diner in Queens. And that's when I first started observing them together.

As for my relationship to the material, other than the fact that it's a good story, and a story I had memories about, it was a story to which I related completely, as I think anyone who's ever been in love and had their heart broken would. What are these things that we do when we are hurt? So deep down, I understood it. Later, as I learned more about their lives, there were other things that I could relate to there; that sense of being alone.

I initially wanted to do this as a narrative feature, and at one point I went down that path. I spoke to Erin Cassandra Wilson (?) about writing it, I had an idea of something like a hybrid between a feature and a doc, and eventually I realized, "well, I think I'm learning more as a documentary filmmaker, so let me pursue it that way."

Describe your first meeting with Burt Pugach.

Dan Klores: I met with Burt about two and a half, three years ago, I'm not quite sure. It was an interesting lunch. He brought Linda, to the diner they always go to, it's the same diner as in the movie, actually. You know, when you first meet Burt, he comes across as a nice old guy. But after a while, you sit there with him and his wife, and he doesn't stop, keeps going on and on. I thought there was something a little off, in the sense that here I am, I'm buttering her toast, and I'm putting on her coat. It was all a little too much about Burt.

There was a great deal of research that was necessary to pull all this together. Can you talk a little bit about that process?

Dan Klores: The whole process is a combination of fun and frustration. The research for this was rigorous. You hire detectives when you do these things that are "based on a true story," if you will. I don't think there's a newspaper or magazine clip about the story that I did not read. I'm very, very, very deliberate and I sort of keep everything I do, also. I don't use a computer, so everything I do is on a yellow legal pad. I not only read everything, but I take notes. Then there was the book about Burt and Linda by Berry Stainback. So I not only read the book, but I take diligent notes. And from that, I learn who I need to speak to. From the beginning I keep a list of all the possible people I need to interview, and I also keep a list of every conceivable image I may need, on my yellow legal pads. Right from the beginning I understood I was going to need records from the courts, I'm going to need records from the police, records from the physicians, from the prison system. So now I have all those things and a list of characters I need to speak to, and then I go after it all.

So part of this was sort of fun. I'm friends with Mayor Giuliani, and he had opened his business a year or two after I started. He loaned me some of his guys, his ex-New York City detectives, and we met frequently. They were able to-I didn't ask how-secure all sorts of court and police records, things that are at what they call "the morgue," from the late 50s, early 60s. In addition to all this, I am allergic to old print, and I couldn't keep these things, so I had to go to this place to look at boxes and boxes of court records, piled up to the ceiling, and, wearing gloves, take notes, and make copies of all the things I might need. And I knew someone at Bellevue, so I got some records from Bellevue. Things like mug shots, and police records - I was able to get all those things. I found Larry Schwartz through Giuliani's people. You think it's easy finding a Larry Schwartz in America? I found out Burt's first wife had passed away recently. Ironically, she lived up the block from me in New York. She had lived between 80th and 81st, and I live on 80th. Then I found her widower, and one thing leads to another. From the widower, who wouldn't talk to me on the record, I found the first wife's sister. I found that Burt's daughter had died-Burt didn't even know that-in 1994. From the widower, whose name is Max, I found Janet Pomerantz, whom I didn't even know existed. There was no record of him having an affair with a secretary.

And then Linda and Burt were very open. I mean, they weren't sophisticated enough to say, "well, you should find so and so," but one thing led to another. I read about the friend, Rita Kessler. Rita Kessler turned me on to Joyce Gurriero, then I found out about Rusty Goldberg. Through my interviews we'd find one person after another.

For how long a period of time did you interview Burt and Linda? How did you structure those sessions?

Dan Klores: I interviewed Burt and Linda a number of times. The first time probably lasted about four hours, at their home in Queens. [Producer] Fisher Stevens was very helpful in that he recommended a DP named Wolfgang Held, a very talented guy. And one of the things I'm not really good at-I'm getting a little better-is lighting my shots. Hopefully, I learn more on each film. Fisher and Wolfgang are terrific at that. I wanted the interview in their apartment. I knew exactly where I wanted to go. I'm very, very well-prepared before I go in. I totally understood that if I'm going to get this out of Linda, Burt cannot be there. And I also understood that if Burt was going to open up, Linda could not be there. Likewise, I always had the thought that the only time I want them together is when they're going to talk about the 1996 affair that Burt had. I thought, that's going to be cool, different-having a husband and wife sit there together, talking about an extramarital affair. So I planned all of that out. I wanted a crew of only women, with the exception of Wolfgang and me. I didn't want any other men in that apartment with Linda. I'm pretty sure I interviewed Linda first. And I said, "Burt, you're not coming back." I got there at 8:00 in the morning, and I said, "you're not coming back, come back when it's 5:00, or 6:00...It's gonna be a complete day." And he was a like a cat scratching the door, at 10.30 the key was in the door, and then at 12:30, the same thing.

Linda was great. She was very open, very honest, it was very moving. And the only thing she wouldn't do, the last thing I asked her to do during the interview was to take off her glasses. And it was the moment that broke my heart. She said, and I'm paraphrasing her, "I won't take them off. Even for you. I have a glass eye, and the other eye is inverted, so I have to look like a freak." That's what she said.

The thing about Linda which was funny was part of her was like a little girl, "What sunglasses should I wear?" She'd lay out three or four sunglasses and ask the women on the crew. And she smoked like a fiend. She is not allowed to smoke because she has a heart condition. She lit her own cigarettes, and because she's blind it was very interesting, she'd miss with the match, and then move that match back and forth until she lit her cigarette-a match, no lighter. She's a dame - a dame.

When I interviewed Burt, it was longer. I limited that to six hours. Quickly I realized that with Burt, if I treat him with respect, which of course I would, I'm going to be able to go everywhere I want. Everywhere. And I did. Because there's a feel for the process - there's a pace to it. You want your subject to open up; there's a seduction going on. But it was pretty clear that Burt's rules were different, which was good for me. The only time he got upset is when I asked him about being in prison all those years, whether he had any sex with men... He really got angry about that, and was adamant, "no, no, no, no way. Somebody once gave me a note, and I told him I'd kill him if he ever gave me a note again." But on the whole, he was just fine. What I realized, was, I'm goin' for it. He told me about his suicide attack. Well, I asked about it, I asked him to let me see his wrists. The one thing I was sort of proud of was when he said he'd rubbed blood all over his face, I asked him, "what temperature was the blood?" He said, "oh, the blood was warmer than I thought."

And then when I interviewed them together about the affair, that too was very strange. Burt was very concerned with the injustice of his prosecution. Adamant. He came back to it time after time after time, and I asked him, "Well, Burt," and this was all in front of his wife, "you seem more upset with the injustice of the prosecution of this, than you are with the fact that you cheated on your wife." That was my question! He looked at me, and he said, "well, that's a loaded question - but you're right!" It was great!

One of the great things about the experience of watching CRAZY LOVE is all the twists and turns in the narrative that are revealed as we progress through the story. In editing the film, how did you think about structuring those moments where you sort of turn the tables on the audience?

Dan Klores: This was a pretty easy film to make. Of course it had all of the anguish, trials, errors, frustrations, etc., but I had outlined my three acts early on, scene by scene, and I had understood that there were going to be different reveals at different times. So what I wrote as a script before I gave it to the editors-knowing that you go through this big upheaval once you start editing-the form of it was pretty consistent with what I wrote. I wanted to begin with the innocence, this romance, and then quickly come to the psychological disabilities of their childhoods, and then come back to the romance. The reveals are all almost exactly where I wanted them to be. Dave Zieff is a great editor, a pleasure to work with, and he built a lot of scenes, he made a lot of scenes much better, and he's great with imagery and music. But in terms of the script, the end product is pretty consistent with the script. And I write every line, every line. The cut I originally edited in the Avid was probably only about two and a half hours, 2 hrs and 40 min. Whereas now, I'm doing a film, a two-part film, that's 3 hours and 15 minutes, and I just finished writing it, just got it into the Avid, and it's seven hours! Maybe it will have to be a three part film.

But those reveals were there. I knew, "I'm going to get you here." The first one, the fact that he's married, that was a little frustrating, because I wanted it 18 minutes in. In the film it's 20 minutes in. I tried and tried and tried to get there quicker. When you lose two minutes, it's a lot.

Besides Burt and Linda, there are a number of other terrific characters in the film. Can you talk a little bit about them?

Dan Klores: There are some great characters in the film, aside from Burt and Linda. They're all different. Some of them reminded me clearly of my parents' generation. So it was easy for me to talk to some of them. Sylvia Hoffman, Linda's first cousin, is a very sweet, kind lady. She still lives in Brooklyn, she's an orthodox Jew. She lives in the neighborhood, near Flatbush. She had a hard life, two children, lost her husband in a car accident when the kids were one and three; very open. Rita Kessler, the woman with the tan, she's a character. I thought she and Fisher [Stevens] were dating or something... I think she had a crush on Fisher, maybe Fisher had a crush on her. It's the second movie of mine that Jimmy Breslin is in, and that's always great. You can't use him too much.

People came through. Only two or three people I interviewed didn't make the film. I found a cousin of Burt's, named Barney Pugach, who lives on Long Island, but wasn't really giving me too much - though he told me his wife would never let Burt be their babysitter. Berry Stainback, the author, was good. Everyone was good; the lady cop, Margie Powers. It wasn't easy finding her, she'd retired to California. Her house burned down, and she now lives in a little place in South Carolina. Her husband is an ex-cop. I just called her up.

There was one other part I had wanted in the film but didn't use. I went down to Florida to interview my parents, because I had this whole idea about love and elderly romance. I interviewed my parents and four of their friends in this community where they live. But I ended up having to cut my own parents out of the film.

This is your fourth movie in the last five years. Where does CRAZY LOVE fit in with your other films?

Dan Klores: It's the same thing. I'm interested in stories about injustice, about love, about loss. That's what I'm interested in. Viva Baseball! is about the Latino experience in baseball, so what's it all about? It's about injustice. In The Boys of 2nd Street Park, the park is really a metaphor for a generation that suffered. The idea that we would be able to live in a safe place, and then the counter-culture; it's basically my story... Drugs and love and music and sex and rock n' roll, and then whack, the war came, and drugs got really heavy, and that's what happened. So the film follows six guys, and some turned out fine, and others are now dead. That's my story. Ring of Fire clearly is about injustice, and discrimination, and love and loss. It's about the loneliness, the isolation of this six-time world champion who has this incredible secret-that he's gay, and has killed somebody-and it humiliates him.

CRAZY LOVE is one of those stranger-than-fiction stories. An extreme case, if you will, about some extraordinary people. What does it have to say to the rest of us? What can take away from it?

Dan Klores: I think the film poses a few things. For one thing: Why? Why would she go off with him? That, to me, is the most interesting question. It's far from a simple analysis. I think Janet Pomerantz says something in the film which is universal: "When we get hurt," and I'm paraphrasing her, "we all think about doing something to the person that hurts us, but he Burt actually did it." I think there's a basic truth to that, if we're honest, uncomfortably honest. But why? And that to me is a very interesting conversation.

CRAZY LOVE feels very rooted in a specific period, a different era. Do you think there's something specific to this time and place that's linked to Burt and Linda's story? Was there something about that time that made their story somehow more feasible?

Dan Klores: Well, their story is a little easier to understand in the time in which it took place. It was a time when women were completely unprotected. There wasn't anything in the psyche of the people, of authorities, to protect women. This was pre-feminism, a long time before people started thinking about protecting women. There was no such thing as "stalking." It was a word, but it didn't pertain to men following women and doing something mean, or unlawful or harmful. No such thing. It didn't exist.

The story is also rooted in a time when a woman had no chance. Following Linda's complaints, the idea that Burt was a lawyer, was akin to royalty and immunity. The words, "lawyer," and "doctor," were, in the community of New York, the community of this city, dreams come true. A lawyer was to be listened to, and honored. So here's this woman making complaints and the cops would say, "we can't do anything about it." I was stunned by this, yet loved the idea that it would make it into the film. That's a part of the times, very much a part of the times.

At the time the case first became news, I was only nine or ten, but these things become a part of you. I grew up with that sense of, "My God, you have a lawyer in your family?" You'd go to him-I was going to say him or her, but there were no "her" lawyers-you'd go to him and the guy could be an negligence attorney and you'd go to him for divorce, or you'd go to him when buying a business, or whatever. It didn't matter, they'd do everything. Lawyers could do everything.

Also specific to the time was this idea about the nightlife that Burt showed Linda. This was big; you have to understand; they lived in the Bronx. I related to that because I grew up in Brooklyn. When you'd go to "The Latin Quarter," where he took her, or "The Copacabana," this was... you might as well have been talking about Paris! This was something that you could never reach. We'd refer to this borough of Manhattan, we'd refer to it as "the City." It was a place that your parents would maybe go to work, nothing else. My parents didn't work there, no way. The City. So the idea that he would take her, this girl from the Bronx, to these places, the idea that he was a lawyer, that he had a Cadillac convertible-a Cadillac! That he had his own home at Scarsdale! Scarsdale was like, are you kidding me? It was beyond the idea of Long Island, of Levittown, or Jersey. It was the height of suburbia, it was synonymous with wealth. And an airplane? So this sheltered little girl, who grew up essentially in foster families, with only women - my god! What was she going to think?

There's also the tabloid nature of the story at that time. When I grew up, you waited till 6:00 or 6:30 every night, for the papers-you didn't call them tabloids-the papers came out. If you were lower middle class or poor, in the boroughs, you'd be interested in the afternoon baseball scores, or maybe you'd follow the track results. At six, seven years old, it was a big thing: "Danny, get the papers." Six, seven years old, you'd go out by yourself, with the money, get the papers, and bring 'em back home. At those newsstands, there'd be thirty, forty men, standing there, waiting for the papers to be delivered because they'd all be looking for the scores and the track results. The papers were big. And you believed anything that they said, anything they said.

Those were days when The New York Post was a liberal paper. That was a major liberal paper, owned by a woman named Dorothy Schiff. In fact, most working class families were, Democrats, a lot of liberal Jews were Democrats, so we bought The Post. The News and The Mirror were Hearst papers, and they were the sensationalist tabloid papers, and they were for the other working class in New York, the Irish and the Italians. And The [New York] Times, we didn't get The Times. We got The Times on Sunday, and that was a special day. "Get The Times," and that meant something. It was like, "Whoa, your father reads The Times?" The papers were almost holy.

MORE