Harold Ramis Year One Interview

RAMIS SATIRIZES BIBLICAL TIMES.

EXCLUSIVE Harold Ramis, Year One Interview by Paul FischerTo call Harold Ramis a true icon of American comedy is an understatement. This versatile comic talent wrote for Chicago's renowned Second City troupe and the National Lampoon radio show before co-scripting the antic fraternity house romp, "National Lampoon's Animal House" (1978). Harold Ramis worked as a mental ward orderly and wrote jokes for PLAYBOY before starting his show business career.

He teamed with John Belushi, Gilda Radner, and Bill Murray on "The National Lampoon Show," but when it came time to organize The Not Ready For Prime Time Players for NBC's "Saturday Night Live" in 1975, he was not asked to join the company by Lorne Michaels. Instead, he applied his comic abilities to the scripts for "Animal House" and the similar "Meatballs" (1979), both of which employed "SNL" cast members (John Belushi and Bill Murray, respectively). Harold Ramis has frequently teamed with comedian Rodney Dangerfield (e.g., TV specials and 1991's animated "Rover Dangerfield"), producer-director Ivan Reitman and especially Murray. Harold Ramis moved to the director's chair with "Caddyshack" (1980, featuring both Dangerfield and Murray), followed by "Stripes" (1981), a Murray vehicle produced by Reitman.

Working with Dan Aykroyd, he shaped the script for the comic blockbuster "Ghostbusters" (1984), which Reitman helmed and which featured Aykroyd, Murray, Harold Ramis and Ernie Hudson as parapsychologists out to rid Manhattan of bizarre apparitions. The inevitable 1989 sequel, "Ghostbusters II", though proved less enchanting and less successful. Throughout the late 1980s, the bespectacled Harold Ramis carved a secondary career as a character player, making appearances as Diane Keaton's live-in lover who leaves with she takes in a child in "Baby Boom" (1987) and offered a somewhat dramatic turn as Mark Harmon's former childhood buddy in "Stealing Home" (1988). Returning behind the camera, he had a surprise hit with the romantic comedy "Groundhog Day" (1993). "Stuart Saves His Family" (1995), based on a sketch from "Saturday Night Live", however, proved less impressive to audiences, although it had a few amusing moments, many provided by writer-star Al Franken. "Multiplicity" (1996) offered a plethora of Michael Keatons as the actor played a harried businessman who allows himself to be cloned.

After a cameo as Jack Nicholson's psychiatrist in "As Good As It Gets" (1997), Harold Ramis tackled the popular comedy "Analyze This" (1999) a canny mismatched buddy film which cast Billy Crystal as a therapist who becomes embroiled in the affairs of one his patients, mob boss Robert De Niro--Ramis and his cast would later reunite for the l2002 sequel "Analyze That." Next up was "Bedazzled," a 2000 update of the original 1967 British comedy penned by Peter Cook, in which a hopeless dweeb (Brendan Fraser) is granted seven wishes by the Devil (Elizabeth Hurley) to snare the girl of his dreams in exchange for his soul. Another minor acting gig followed in the low-profile comedy "I'm with Lucy" (2002) before Harold Ramis attempted a semi-radical shifting of gears with "The Ice Harvest" (2005), a bleak film noir layered with pitch-black comedy, featuring John Cusack as a small-town mob accountant trying to survive a dangerous, icy Christmas Eve after he and his accomplice (Billy Bob Thornton) steal millions from his client (Randy Quaid).

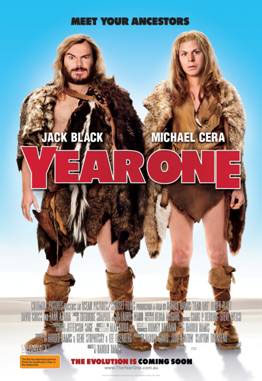

Harold Ramis returns behind the camera with the Biblical satire Year One with Jack Black and Michael cast as two men wandering aimlessly through Biblical times. Harold Ramis talked exclusively to Paul Fischer about the film, comedy and yes, the inevitable talk of a third Ghostbusters.

QUESTION: You wrote this, as well as directed it and I'm just wondering, has it always been comedically interesting for you to explore time, and the notion of time and the fish-out-of-water story that is part of this movie?

QUESTION: You wrote this, as well as directed it and I'm just wondering, has it always been comedically interesting for you to explore time, and the notion of time and the fish-out-of-water story that is part of this movie?HAROLD RAMIS: Well, I've always been interested in history, and the ancient world. I've always tried to read Genesis, and the Bible itself, as history. And someone - a real scholar once said that the Bible starts off as mythology, then it becomes legend, and then it becomes history. And you can pretty much peg where the history starts. Where it starts to actually correlate with the known history of the Middle East, and everything. But when it's still in the myth and legend phase - you know, I started my own interpretations. You know, Genesis is very sparse. There's very little description, and very little explanation of anything. So I thought, "Well, I'm free to make up my own interpretation." You know, about Adam and Eve, about Cain and Abel. About Abraham. All those stories. So that's what I did.

QUESTION: It's a very vast period. How challenging was it for you as a writer to structure a script that dealt with a very sort of relatively focused period of history, in such a short amount of screen time?

HAROLD RAMIS: Well, I knew right away I was going to take the liberty of conflating time, you know? Of just compressing it all. Someone said to us, after one of the test market screenings - someone in the focus group said, "Well, how can they meet Cain and Abel and Abraham?" There's - they lived 1000 years apart. And I said, "Oh, you mean the real Cain and Abel. This is - this is a different Cain and Abel." Because - you know, that's what I mean about it being legend. There's no dates. We don't have dates for Cain and Abel. We have generations discussed in the Bible. That's how time is - but even in these generations that are described in the Bible, people are living hundreds of years. I'm - I tend to think more practically than that. I'm guessing people weren't living hundreds of years. And that you can't really trust time in the Bible. It's hard to trust time in a document that tells you that the Earth was created in six days.

QUESTION: And did you always feel the Bible lent itself to satire? I mean, was it always a ripe source for satire?

QUESTION: And did you always feel the Bible lent itself to satire? I mean, was it always a ripe source for satire?HAROLD RAMIS: Well, yeah, in a way. There's very little judgment in Genesis. You know, there are great morality stories. Certainly the Gospels are terrific morality tales. A lot of the Bible is political. It's about the politics of Judea and Israel and the Middle East. Certainly once the kings take over. A lot of it is the history of the Hebrew people, their migrations - you know, from Canaan into Egypt, and back to Canaan and the Diaspora, into Babylon and Persia, and all that stuff. But the early stuff is really sketchy, kind of tracking the early history of mankind. The progression from hunter-gatherer to Iron Age, localized farming to settled agriculture and the beginnings of real civilization. And that's the story I was telling. That's what I wanted to track.

QUESTION: Did you find it fun to give this film a Jewish perspective? I mean, do you see this as much a comment on Judaism as it is on history?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah. I mean, to the extent that - you know, in Western civilization, the history of Western civilization begins with the history of Judaism. Americans don't study - the Western people don't study the Gilgamesh epic as the first story, although it's probably the oldest epic story. You know, for most Westerners, it goes from the Old Testament to Greek and Roman history, and then the Roman era. And then, of course, suddenly we're into the Christian world. And that kind of ignores a lot of important culture and civilization. Like I said, the old testament is so sketchy, there's not much to really satirize. The satire is about human behavior. And I'm - my guess was that there were always people like us, like Jack Black and Michael Cera, even as far back as 1500 years, hunter gatherers, or back in the beginnings of settled agriculture. There had to be slackers then, you know? There had to be funny people then.

QUESTION: Do Jack and Michael represent, to you, the new generation of contemporary comedian, of comic film actor?

QUESTION: Do Jack and Michael represent, to you, the new generation of contemporary comedian, of comic film actor?HAROLD RAMIS: Well, they are - you know, they're a generation apart. Jack is 20 years older than Michael, almost.

QUESTION: I guess it's true, yeah.

HAROLD RAMIS: So, they kind of represent two generations. But in popular culture terms, there are a number of terrific people out there, and Jack and Michael are certainly prominent among them. But there have been a lot of great comedies in the last ten years or so. And you see a lot of the same faces turning up over and over. And certainly Judd Apatow's been connected to a bunch of them. Todd Phillips, and that group. And - I'm going to leave out a lot of names. Tom Shadyac. John Hamburg. The Farrelly Brothers. You know, all these guys are turning out good films. I'm leaving out the guy who directed - Jay Roach. These are the people who are active today making comedies. And now Greg Mottolla, a lot of good people doing comedy now, and everyone knows everyone now. So, it feels like a generation. It's a small club.

QUESTION: Has your own comic sensibility changed dramatically in the last three decades? I mean, do you think your sense of humor has changed with the times, or do you think that your basic sensibilities as a comic filmmaker and writer have remained pretty much the same?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah - I mean, I don't know how much I've changed, or evolved as a writer or a human being. I have more experience in the world. Maybe I'm calmer about certain things. Maybe - you know, a different perspective. I'm 64 years old. You know, some of these guys are in their 40s, the older ones. The younger ones, down to 18, 19 years old. So, yeah. I see the world differently. That's an inevitable consequence of getting older. But what makes me laugh has not really changed. And whatever standards I have have not really changed. I like a comedy that's brave, fresh, and smart.

QUESTION: Has the business of movie comedy changed? I mean, when you write a script now, are there different parameters that you have to work within a studio system that presumably is not the same as it was in the '70s and '80s, when you started?

QUESTION: Has the business of movie comedy changed? I mean, when you write a script now, are there different parameters that you have to work within a studio system that presumably is not the same as it was in the '70s and '80s, when you started?HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah. Well, I think - you know, certain things haven't changed. You know, still decisions are made about R-rating, or PG-13, which do affect the kind of comedy you're doing. But - you know, comedy's no different from any other genre in Hollywood, in that - you know, everything is now driven by marketing. It's inevitable, with movies costing so much to make now. The studio - and I don't blame them for this - they have to know that they can sell them, before they'll make them. So it's not even about their taste. The people who decide what movies get made - they're not stupid. They're smart. They've all been to good schools. They're as smart as we are. They have good taste themselves. Movies they would choose to see are not necessarily the movies that get made. But they know they have to sell them. And that dictates a lot to them. So, if you're going to make a popular comedy now, and it may include high-priced actors and a huge mass-marketing campaign, if you're going to open in 2000 theatres, you have to market this thing all around the country. That means expensive television advertising, all kinds of expensive promotions. So you've got to have something that a lot of people are gonna want to see and enjoy. But that's tough. You can't do a movie for a very small segment of the audience, unless you're willing to do it pretty quickly and for very little money.

QUESTION: What kind of aspirations did you have when you were very young, Harold? Was it just writing? Was it performing? Was it a combination of the two? I mean, where did this desire to be funny come from?

HAROLD RAMIS: You know those commercials for "the world's most interesting man?" I wanted to be that guy. I wanted to be - I wanted to do it all. You know? And I meant everything in life. I wanted to experience everything. But - you know, career-wise, after college, it really came down to, I wanted to write, I wanted to act, and I wanted to direct. And it started with a childhood affection for - mainly for comedy, but for adventure, too. I grew up on television and films. This is what I wanted to do.

QUESTION: Did you ever imagine that at this time in your life, you would still be as immersed and involved in comedy as you were when you were starting out, really?

QUESTION: Did you ever imagine that at this time in your life, you would still be as immersed and involved in comedy as you were when you were starting out, really?HAROLD RAMIS: Well, you know, when you grow up watching popular entertainment - I watched Rodney Dangerfield - you know, perform until he was too old to remember his lines. People worked 'til their dead. Once someone's popular, there's no reason an actor has to stop acting. And I'm just - I've certainly seen directors who have - you know, pursued their careers right to the ends of their lives. Robert Altman was - you know, working on a new film when he died. John Huston directed right up to his death. Sidney Lumet just did a great film a couple of years ago that - you know, he's got to be 80. There are plenty of examples of both performers, writers - you know, some of our best novelists are still writing into their 80s. Screenwriters - there's probably not, because there's a certain amount of ageism in the business. But certainly among actors and directors, age is no barrier to anything.

QUESTION: You've been involved in some of comedy's most iconic films. Do you - obviously you didn't see that at the time that these films were being made. But when you look back on your career, on films like Meatballs and Animal House, and obviously Ghostbusters, et cetera, what do you see now with the benefit of hindsight?

HAROLD RAMIS: Well, you know, movies, to some extent, are a projective device, you know? They don't change. Once the movie is done, it's done. It doesn't get better or worse. So when I look at these movies myself, I see - you know, I see successful moments. I see scenes that work. I see movies that work, some better than others. But I see a lot of mistakes. I see things that - you know, where it could be better. To me, they all have a lot of flaws. I'm not saying I'm ashamed of anything. But - no, I can cringe a little bit at certain moments. Wish I could do it over. Which I'd had a better idea at the moment. But it's - the public has embraced these things, and projects a lot of their own feelings onto these films, you know? It doesn't - just because people love a movie doesn't make it a masterpiece, you know? I'm not gonna contest anyone's affection for Caddyshack. It's not the best-made movie in the world.

QUESTION: But it's a fun film, though.

QUESTION: But it's a fun film, though. HAROLD RAMIS: It's fun. It's very entertaining. And - you know, it works on a lotta levels. But I have no illusions that - you know, it's a masterpiece. And - you know, to whatever extent people feel the need to declare certain things legendary, or - you know. It just tells me how much those films mean to them. And that has a lot to do with who they were when they first saw them. What are the issues in their lives? That's what I mean by movies being a projective device, you know? So when someone comes up to me and says, "Oh, I love Caddyshack, man," I know it's a certain kind of person. Another person comes up to me and said, "Oh, Groundhog Day changed my life," I know that's a different kind of person, you know? Or - you know, whatever film they mentioned, I realize how much they've projected onto the film.

QUESTION: Now, there - there is supposed to be this remake happening of Meatballs.

HAROLD RAMIS: I've heard that. I have no information about that. It turned up on IMDB one day on my profile, and I've never said a word, or heard a word about it.

QUESTION: I mean, my question would be, "Why," of course. Because I don't understand why -

HAROLD RAMIS: There've been three sequels to Meatballs I had nothing to do with. I've never - my whole involvement in Meatballs probably lasted a month.

QUESTION: What about the much-written about, talked about, and ballyhooed Ghostbusters sequel?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah. Well, Dan Aykroyd - you know, kind of kept it alive all these years. And - it finally got to a point where everyone has said they would do it, if there's a great script and the studio proceeded to - you know, engaged us to get that process going. And we kind of hammered out a story with the two young writers who worked on t finally got to a point where everyone has said they would do it, if there's a great script and the studio proceeded to - you know, engaged us to get that process going. And we kind of hammered out a story with the two young writers who worked on Year One with me, Lee Eisenberg and Gene Stupnitsky. They're writer-producers on The Office. And they're gonna finish a first draft eventually, and we'll see where we are. No one's committed anything. You know, there's no casting, there's no director. There's just - just the desire to look at a script.

QUESTION: I guess Bill was one of the biggest holdouts on moving this forward. What do you think changed his mind?

QUESTION: I guess Bill was one of the biggest holdouts on moving this forward. What do you think changed his mind?HAROLD RAMIS: I don't know that he was really holding out on anything, because there had been no concerted effort to do this, really. There'd been talk about it at one point, and it didn't look like it was possible to make a financial deal. And that was all business. But at the time, there was no real idea, and no real creative will to do it.

QUESTION: The first one was pretty much ahead of its time. You couldn't make that first one now the same way, for the kind of mon-I mean, today, that would be extraordinarily expensive, wouldn't it?

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah. It wasn't super-expensive, in its time. I don't know what the economics would be of doing those effects now. The second movie was - the first movie, all the effects are optical. The second movie, they were all digital. There'd been a complete revolution in the business in between - in the four years between the films. But I don't know - I never - you know, I couldn't even tell you what either of them cost, budget-wise.

QUESTION: What do you hope to do next, assuming that you'll do something before Ghostbusters 3?

HAROLD RAMIS: I'm just relaxing. You know, we read scripts that people send us. You know, I have one pretty worthy spec script that I wrote. That I could turn into a movie - I'm not sure it's right for that. You know, I wait for some vital interests to awaken in me, whether it's passion for an idea, or just - I really have to want to do something badly to get going these days. Maybe it's always been true. I really - you know, I've never worked just to work.

QUESTION: In fact, do you think you still have the same passion for this business?

HAROLD RAMIS: I did for Year One, that's for sure. You know, it's - I really wanted to do that film in that setting, tell that story, with these characters. And it was so much fun to do. I'm still excited about it. And whatever the outcome, it's been a great, great experience for me. And, you know, I'm looking for the next great experience. But for me, it starts with a really great idea, and some really great writing.

Year One

Starring: Jack Black, Michael Cera, Oliver Platt, David Cross, Hank Azaria, Paul RuddDirector: Harold Ramis

Genre: Comedies

When a couple of lazy hunter-gatherers (Jack Black and Michael Cera) are banished from their primitive village, they set off on an epic journey through the ancient world in Columbia Pictures'...

When a couple of lazy hunter-gatherers (Jack Black and Michael Cera) are banished from their primitive village, they set off on an epic journey through the ancient world in Columbia Pictures' comedy Year One. Harold Ramis directs.

The screenplay is by Harold Ramis & Gene Stupnitsky & Lee Eisenberg (The Office) from a story by Harold Ramis. The film is produced by Harold Ramis, Judd Apatow, and Clayton Townsend.

MORE