Malik Bendjelloul Searching For Sugar Man Interview

Malik Bendjelloul Searching For Sugar Man Interview

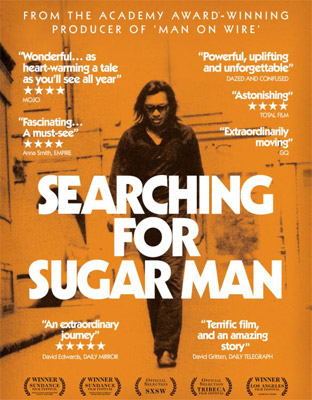

Cast: Rodriguez, Malik Bendjelloul

Director: Malik Bendjelloul

Genre: Documentary

Running Time: 85 minutes

Synopsis: In 1968, two producers went to a downtown Detroit bar to see an unknown recording artist – a charismatic Mexican-American singer/songwriter named Rodriguez who had attracted a local following with his mysterious presence, soulful melodies and prophetic lyrics. They were immediately bewitched by the singer, and thought they had found a musical folk hero in the purest sense – an artist who reminded them of a Chicano Bob Dylan, perhaps even greater. They had worked with the likes of Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, but they believed the album they subsequently produced with Rodriguez – Cold Fact – was the masterpiece of their producing careers.

Despite good reviews, Cold Fact was a commercial disaster and marked the end of Rodriguez's recording career before it had even started. Rodriguez sank back into obscurity. All that trailed him were stories of his escalating depression, and eventually he fell so far off the music industry's radar that when it was rumored he had committed suicide, there was no conclusive report of exactly how and why. Of all the stories that circulated about his death, the most sensational – and the most widely accepted – was that Rodriguez had set himself ablaze on stage having delivered these final lyrics: 'But thanks for your time, then you can thank me for mine and after that's said, forget it." The album's sales never revived, the label folded and Rodriguez's music seemed destined for oblivion.

This was not the end of Rodriguez's story. A bootleg recording of Cold Fact somehow found its way to South Africa in the early -70s, a time when South Africa was becoming increasingly isolated as the Apartheid regime tightened its grip. Rodriguez's anti-establishment lyrics and observations as an outsider in urban America felt particularly resonant for a whole generation of disaffected Afrikaners. The album quickly developed an avid following through word-of-mouth among the white liberal youth, with local pressings made. In typical response, the reactionary government banned the record, ensuring no radio play, which only served to further fuel its cult status. The mystery surrounding the artist's death helped secure Rodriguez's place in rock legend and Cold Fact quickly became the anthem of the white resistance in Apartheid-era South Africa. Over the next two decades Rodriguez became a household name in the country and Cold Fact went platinum.

Despite his enormous popularity, Rodriguez's personal life remained a mystery to almost all of his listeners. Various South African journalists and fans tried to uncover the truth about his life, and yet almost nothing was discovered – even about his legendary demise.

When his second album was finally released on CD in South Africa in the mid -90s, two white South African fans – 'musicologist detective" Craig Bartholemew and record shop owner Stephen 'Sugar" Segerman – decided to join forces in an attempt to get to the bottom of the enduring mystery of who Rodriguez was, and how he died. The investigation they embarked on was daunting; they initially found only inconsistencies and dead ends. Taking their cue from Watergate, they finally came up with a strategy to 'follow the money," figuring that if they could trace Cold Fact's royalties, they might have a chance of uncovering the truth. They looked for clues in the only place available – Rodriguez's lyrics. A mention of a suburb in Detroit finally led them to track down one of the original producers of Cold Fact, Mike Theodore. This contact uncovered a shocking revelation that in turn set off a wild chain of events that was stranger – and more exhilarating – than they could ever have expected.

Release Date: October 4th, 2012

Director: Malik Bendjelloul

Genre: Documentary

Running Time: 85 minutes

Synopsis: In 1968, two producers went to a downtown Detroit bar to see an unknown recording artist – a charismatic Mexican-American singer/songwriter named Rodriguez who had attracted a local following with his mysterious presence, soulful melodies and prophetic lyrics. They were immediately bewitched by the singer, and thought they had found a musical folk hero in the purest sense – an artist who reminded them of a Chicano Bob Dylan, perhaps even greater. They had worked with the likes of Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, but they believed the album they subsequently produced with Rodriguez – Cold Fact – was the masterpiece of their producing careers.

Despite good reviews, Cold Fact was a commercial disaster and marked the end of Rodriguez's recording career before it had even started. Rodriguez sank back into obscurity. All that trailed him were stories of his escalating depression, and eventually he fell so far off the music industry's radar that when it was rumored he had committed suicide, there was no conclusive report of exactly how and why. Of all the stories that circulated about his death, the most sensational – and the most widely accepted – was that Rodriguez had set himself ablaze on stage having delivered these final lyrics: 'But thanks for your time, then you can thank me for mine and after that's said, forget it." The album's sales never revived, the label folded and Rodriguez's music seemed destined for oblivion.

This was not the end of Rodriguez's story. A bootleg recording of Cold Fact somehow found its way to South Africa in the early -70s, a time when South Africa was becoming increasingly isolated as the Apartheid regime tightened its grip. Rodriguez's anti-establishment lyrics and observations as an outsider in urban America felt particularly resonant for a whole generation of disaffected Afrikaners. The album quickly developed an avid following through word-of-mouth among the white liberal youth, with local pressings made. In typical response, the reactionary government banned the record, ensuring no radio play, which only served to further fuel its cult status. The mystery surrounding the artist's death helped secure Rodriguez's place in rock legend and Cold Fact quickly became the anthem of the white resistance in Apartheid-era South Africa. Over the next two decades Rodriguez became a household name in the country and Cold Fact went platinum.

Despite his enormous popularity, Rodriguez's personal life remained a mystery to almost all of his listeners. Various South African journalists and fans tried to uncover the truth about his life, and yet almost nothing was discovered – even about his legendary demise.

When his second album was finally released on CD in South Africa in the mid -90s, two white South African fans – 'musicologist detective" Craig Bartholemew and record shop owner Stephen 'Sugar" Segerman – decided to join forces in an attempt to get to the bottom of the enduring mystery of who Rodriguez was, and how he died. The investigation they embarked on was daunting; they initially found only inconsistencies and dead ends. Taking their cue from Watergate, they finally came up with a strategy to 'follow the money," figuring that if they could trace Cold Fact's royalties, they might have a chance of uncovering the truth. They looked for clues in the only place available – Rodriguez's lyrics. A mention of a suburb in Detroit finally led them to track down one of the original producers of Cold Fact, Mike Theodore. This contact uncovered a shocking revelation that in turn set off a wild chain of events that was stranger – and more exhilarating – than they could ever have expected.

Release Date: October 4th, 2012

Interview with Malik Bendjelloul

Question: How and when did you first come across the story?

Malik Bendjelloul: In 2006, after five years making TV documentaries in Sweden, I spent six months travelling around Africa and South America looking for good stories. In Cape Town I met Stephen 'Sugar" Segerman, who told me about Rodriguez. I was completely speechless – I hadn't heard a better story in my life. This was five years ago and I have been working on this film more or less every day since then.

Question: What were your first impressions when you initially heard Rodriguez's music?

Malik Bendjelloul: I had never heard Rodriguez's music when Stephen Segerman first told me about him. I fell so totally in love with his story that I was almost afraid to listen to his work – I thought the chances were very slim that the music would be as good as the story, that I'd be disappointed and lose momentum. I started to listen to it when I came back to Europe, and I couldn't believe my ears – literally. I thought my feelings for the story might have influenced my judgment, and I needed to play it to other people to see if they agreed. Their reactions convinced me – these really were songs on a level equal to the best work of Bob Dylan, even the Beatles.

Everyone calls Rodriguez's music "folk," but I don't think it's any more folk than the Beatles. Rodriguez's songs are all very different. Some are folk, some are rock, some are pop, and some are blues. Just like any great artist – it's hard to categorise, but every song has something different.

Question: Through Rodriguez's story, the film portrays an often-unexamined subject: unrest in the South African Apartheid government from white, liberal Afrikaners. Was this something you learned about while filming?

Malik Bendjelloul: Apartheid was something that was constantly in the news when I was a young, but it seems like ever since Mandela gained power there hasn't been too much talk about that era. It's strange that for almost fifty years – all the way into the mid-nineties – there was a country in the world that was a surviving ideological sibling to Hitler's Third Reich. Mandela implemented a policy of reconciliation, which I think is a very wise philosophy, but I think we still need to know and learn about these times more than we do. I had never heard of any subversive white liberal counter-movement; all of this was new to me.

The Apartheid regime was very racist, but the liberal whites were probably more anti-racist than liberal whites in America at that same time. For the South African liberals it was absolutely no problem that a singer had a Hispanic name and Hispanic looks. In America in that era, if your name was Rodriguez you were supposed to play Mariachi music. Rodriguez was a serious challenge to the white rock scene – the Lou Reeds and the Bob Dylans of this world – which was still very much an exclusive members club in Europe and America at this time.

I did random vox-pops in the streets of Cape Town – every second person knows of Rodriguez, no matter their age or sex.

Question: What were the biggest challenges in making the film?

Malik Bendjelloul: The hardest thing was to get the right people to believe in the project. I thought it was evident that the story was good – had it been conceived by a screenwriter you would have thought that it was too much, too unbelievable to make sense. I thought that the fact that this really happened – and the way it happened – would be enough to attract investors. But in the end the story attracted everyone except for the investors. Maybe it was because I was a first-time director.

I still have an email in my inbox from a renowned film financier who I sent the film to when it was 90% ready. He told me that he couldn't see a feature film in the material, that at best it could be enough for a one hour TV documentary and, consequently, he couldn't give me any funding. I was devastated, I thought that without this money I was lost and would have to give up the film. I hadn't received a salary for three years and needed to find myself a proper job instead. But I also felt it would be such a waste not to complete the film. I still had to find a way to pay for an online editor, a composer for the score, and an animator for the illustrations. These were expensive elements needed to complete the film, and I knew I wouldn't be able to afford it.

Then one day, I decided to see what I could do on my own. I started to paint the animation myself. For one month I was sitting painting with chalk by my kitchen table. I had never painted before in my life, but I thought my efforts might be good enough as sketches, and would reduce the work for a real animator later. And then I tried the same with the music. I used $500 midi software and composed a dummy for the original score. And I edited the film as well as I could on Final Cut.

And then my luck turned – I got in touch with producers Simon Chinn and John Battsek and showed them what I had worked on. They loved the film. They helped me a great deal and had loads of useful creative ideas. When I asked them who should complete the editing, the animation and the music, they surprised me by saying they thought all those elements were already all there. Suddenly, without me knowing how it happened, the film was complete. It was finally done.

Question: How do you feel about the film now? Is it what you imagined it would be when you embarked on it?

Malik Bendjelloul: When I embarked on the project I assumed it would be a half hour TV documentary, which is the type of project I was previously involved in. But I completely fell in love with the story and I couldn't stop working on it. I hadn't spent more than a month on a single project before; I counted the days last week – I've spent a thousand days on this one. After the first six months I had 80% of the film done, the last 3 years have been focussed on completing the last 20%. The difference was like night and day when Simon Chinn and John Battsek came on board. They are so clever, effective and talented. To be honest, their involvement has been worth a year of extra input into the film. It's hard for a first-time director to convince the right people in the power of your story. The first time I called Simon I only reached the receptionist's desk. I asked if I could get three minutes on the phone with Simon and I promised I was going to tell him a story that was "as good as -Man on Wire'."

Question: How do you feel about the film's upcoming premiere at Sundance?

Malik Bendjelloul: It feels wonderful. Sundance was my prime goal from the very start with this film. I was prepared to edit for another year in order to re-submit the film for Sundance 2013 if it was not accepted this year, so I'm thrilled. It's an American story, and I think Sundance is the most appropriate place to premiere the film.

Question: What are you hoping audiences will take from the film?

Malik Bendjelloul: I hope audiences will react emotionally. I think that most filmmakers hope their work will hit emotionally – physically – and not just intellectually. When I see a film or read a book, if I get even just one single goose bump, or one tiny tear in my eye – that's more of a payback than any intellectualising. It's hard to reach an audience in any profound way; people have a lot of built-in barriers. Just telling a story well enough so people can fully engage in the film is a major challenge. If people aren't paying 100% attention, then all the barriers are up.

Question: What have you learned over the course of making the film?

Malik Bendjelloul: I learned that it's possible to live your life on your own terms. Even if it means huge sacrifice, it's your life and you will regret it if you don't try. Rodriguez didn't want to conform to any format or rules. He said what he wanted to say, and then he waited for people to embrace his music and his ethos, and not the other way around. I think that's something we can all learn a lot from. Maybe more success or more money could come by compromising your dreams, but don't go there! Rodriguez used to repeat the adage "you shouldn't take candy from strangers." That could apply to filmmaking. Filmmakers might go to a film institute for financing and think that all problems will be solved, but it comes with sacrifices. Maybe you'll get the money, but maybe it'll be a year too late and you've lost your inspiration and passion. If you want to be true to yourself you need to set your own rules – use your own money, and if you don't have much then make a cheap film. This is much easier with cheap digital technology. If it turns out to be a good film, you can sell it and from the surplus you can make the next film. Times have changed – filmmaking just isn't that expensive anymore. My cinematographer Camilla Skagerstrom won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes last year for a short film she made using $3000 of her own money. She didn't compromise. If you want to make a film, it needs to be your film, made on your terms and with the energy you only can get from the possible misconception that all is possible and all your dreams can come true. Don't wait for the money until you've lost the spark – just do it anyway.

In the same way, Rodriguez eventually found his audience his own way. Why: because he stayed true to his ideals. So much so that it seemed like he was almost purposely hiding his talent and avoiding success. But in the end, it turned out to be the other way around. His creativity was uncompromised and therefore flawless. I think this is really something any artist needs to consider carefully. Their true treasure is their own integrity, dignity, inspiration and passion. Protect this at all costs.

Malik Bendjelloul: In 2006, after five years making TV documentaries in Sweden, I spent six months travelling around Africa and South America looking for good stories. In Cape Town I met Stephen 'Sugar" Segerman, who told me about Rodriguez. I was completely speechless – I hadn't heard a better story in my life. This was five years ago and I have been working on this film more or less every day since then.

Question: What were your first impressions when you initially heard Rodriguez's music?

Malik Bendjelloul: I had never heard Rodriguez's music when Stephen Segerman first told me about him. I fell so totally in love with his story that I was almost afraid to listen to his work – I thought the chances were very slim that the music would be as good as the story, that I'd be disappointed and lose momentum. I started to listen to it when I came back to Europe, and I couldn't believe my ears – literally. I thought my feelings for the story might have influenced my judgment, and I needed to play it to other people to see if they agreed. Their reactions convinced me – these really were songs on a level equal to the best work of Bob Dylan, even the Beatles.

Everyone calls Rodriguez's music "folk," but I don't think it's any more folk than the Beatles. Rodriguez's songs are all very different. Some are folk, some are rock, some are pop, and some are blues. Just like any great artist – it's hard to categorise, but every song has something different.

Question: Through Rodriguez's story, the film portrays an often-unexamined subject: unrest in the South African Apartheid government from white, liberal Afrikaners. Was this something you learned about while filming?

Malik Bendjelloul: Apartheid was something that was constantly in the news when I was a young, but it seems like ever since Mandela gained power there hasn't been too much talk about that era. It's strange that for almost fifty years – all the way into the mid-nineties – there was a country in the world that was a surviving ideological sibling to Hitler's Third Reich. Mandela implemented a policy of reconciliation, which I think is a very wise philosophy, but I think we still need to know and learn about these times more than we do. I had never heard of any subversive white liberal counter-movement; all of this was new to me.

The Apartheid regime was very racist, but the liberal whites were probably more anti-racist than liberal whites in America at that same time. For the South African liberals it was absolutely no problem that a singer had a Hispanic name and Hispanic looks. In America in that era, if your name was Rodriguez you were supposed to play Mariachi music. Rodriguez was a serious challenge to the white rock scene – the Lou Reeds and the Bob Dylans of this world – which was still very much an exclusive members club in Europe and America at this time.

I did random vox-pops in the streets of Cape Town – every second person knows of Rodriguez, no matter their age or sex.

Question: What were the biggest challenges in making the film?

Malik Bendjelloul: The hardest thing was to get the right people to believe in the project. I thought it was evident that the story was good – had it been conceived by a screenwriter you would have thought that it was too much, too unbelievable to make sense. I thought that the fact that this really happened – and the way it happened – would be enough to attract investors. But in the end the story attracted everyone except for the investors. Maybe it was because I was a first-time director.

I still have an email in my inbox from a renowned film financier who I sent the film to when it was 90% ready. He told me that he couldn't see a feature film in the material, that at best it could be enough for a one hour TV documentary and, consequently, he couldn't give me any funding. I was devastated, I thought that without this money I was lost and would have to give up the film. I hadn't received a salary for three years and needed to find myself a proper job instead. But I also felt it would be such a waste not to complete the film. I still had to find a way to pay for an online editor, a composer for the score, and an animator for the illustrations. These were expensive elements needed to complete the film, and I knew I wouldn't be able to afford it.

Then one day, I decided to see what I could do on my own. I started to paint the animation myself. For one month I was sitting painting with chalk by my kitchen table. I had never painted before in my life, but I thought my efforts might be good enough as sketches, and would reduce the work for a real animator later. And then I tried the same with the music. I used $500 midi software and composed a dummy for the original score. And I edited the film as well as I could on Final Cut.

And then my luck turned – I got in touch with producers Simon Chinn and John Battsek and showed them what I had worked on. They loved the film. They helped me a great deal and had loads of useful creative ideas. When I asked them who should complete the editing, the animation and the music, they surprised me by saying they thought all those elements were already all there. Suddenly, without me knowing how it happened, the film was complete. It was finally done.

Question: How do you feel about the film now? Is it what you imagined it would be when you embarked on it?

Malik Bendjelloul: When I embarked on the project I assumed it would be a half hour TV documentary, which is the type of project I was previously involved in. But I completely fell in love with the story and I couldn't stop working on it. I hadn't spent more than a month on a single project before; I counted the days last week – I've spent a thousand days on this one. After the first six months I had 80% of the film done, the last 3 years have been focussed on completing the last 20%. The difference was like night and day when Simon Chinn and John Battsek came on board. They are so clever, effective and talented. To be honest, their involvement has been worth a year of extra input into the film. It's hard for a first-time director to convince the right people in the power of your story. The first time I called Simon I only reached the receptionist's desk. I asked if I could get three minutes on the phone with Simon and I promised I was going to tell him a story that was "as good as -Man on Wire'."

Question: How do you feel about the film's upcoming premiere at Sundance?

Malik Bendjelloul: It feels wonderful. Sundance was my prime goal from the very start with this film. I was prepared to edit for another year in order to re-submit the film for Sundance 2013 if it was not accepted this year, so I'm thrilled. It's an American story, and I think Sundance is the most appropriate place to premiere the film.

Question: What are you hoping audiences will take from the film?

Malik Bendjelloul: I hope audiences will react emotionally. I think that most filmmakers hope their work will hit emotionally – physically – and not just intellectually. When I see a film or read a book, if I get even just one single goose bump, or one tiny tear in my eye – that's more of a payback than any intellectualising. It's hard to reach an audience in any profound way; people have a lot of built-in barriers. Just telling a story well enough so people can fully engage in the film is a major challenge. If people aren't paying 100% attention, then all the barriers are up.

Question: What have you learned over the course of making the film?

Malik Bendjelloul: I learned that it's possible to live your life on your own terms. Even if it means huge sacrifice, it's your life and you will regret it if you don't try. Rodriguez didn't want to conform to any format or rules. He said what he wanted to say, and then he waited for people to embrace his music and his ethos, and not the other way around. I think that's something we can all learn a lot from. Maybe more success or more money could come by compromising your dreams, but don't go there! Rodriguez used to repeat the adage "you shouldn't take candy from strangers." That could apply to filmmaking. Filmmakers might go to a film institute for financing and think that all problems will be solved, but it comes with sacrifices. Maybe you'll get the money, but maybe it'll be a year too late and you've lost your inspiration and passion. If you want to be true to yourself you need to set your own rules – use your own money, and if you don't have much then make a cheap film. This is much easier with cheap digital technology. If it turns out to be a good film, you can sell it and from the surplus you can make the next film. Times have changed – filmmaking just isn't that expensive anymore. My cinematographer Camilla Skagerstrom won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes last year for a short film she made using $3000 of her own money. She didn't compromise. If you want to make a film, it needs to be your film, made on your terms and with the energy you only can get from the possible misconception that all is possible and all your dreams can come true. Don't wait for the money until you've lost the spark – just do it anyway.

In the same way, Rodriguez eventually found his audience his own way. Why: because he stayed true to his ideals. So much so that it seemed like he was almost purposely hiding his talent and avoiding success. But in the end, it turned out to be the other way around. His creativity was uncompromised and therefore flawless. I think this is really something any artist needs to consider carefully. Their true treasure is their own integrity, dignity, inspiration and passion. Protect this at all costs.

MORE